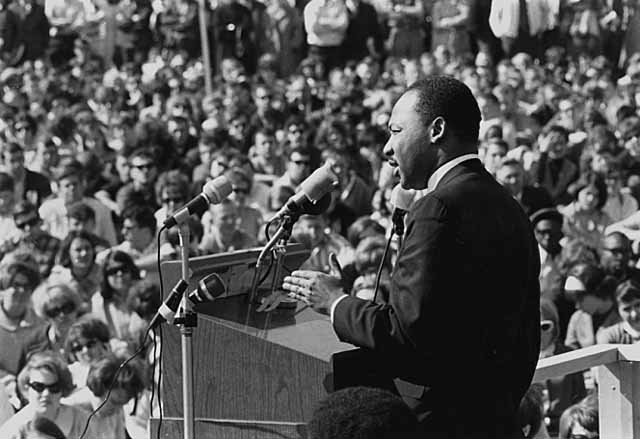

King speaking to an anti–Vietnam War rally at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul, April 27, 1967. (Photo: Wikipedia)

By Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi

King saw his commitment to racial justice and his opposition to the war in Vietnam as integrally connected aspects of a single moral and spiritual demand: “to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation and for those it calls enemy.” He joined the dots to see the triple evil of racism, poverty, and militarism as three manifestations of a pernicious scheme of values that prizes wealth above people.

The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. is best known as the civil rights leader who, in the late 1950s and 1960s, led his fellow African Americans in their nonviolent struggle to end the oppressive Jim Crow policies that reigned throughout the South. His crowning achievement, in this period of his life, was the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965. In recognition of his role in leading these campaigns, King was honored with the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

King’s victory in the fight for civil rights did not bring an end to his commitment to social justice. The same inner calling that drew him to the struggle for civil rights now beckoned him into new arenas that called for a conscientious response. One cause to which King devoted himself was opposition to the U.S. war in Vietnam, which had surged in the late 1960s, with a devastating rise in casualties. The other was the persistence of crippling poverty, which was particularly endemic among African Americans but also beset people of all races throughout the U.S. and around the world.

King saw these manifestations of human suffering—racism, militarism, and poverty—not as isolated and disconnected phenomena, but as overlapping, interconnected violations of inherent human dignity. In his view, they all sprang from a fundamental distortion in values that infected the depths of the soul. Thus the remedy for them—for all three at once—was not merely a change in political and economic policies but a far-reaching moral transformation of human consciousness that extended down to its base.

King is best remembered for his poignant “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial at the famous March on Washington in August 1963. The speech envisioned a future when people would embrace each other without regard for the color of their skin, when even in Alabama, “little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” Despite its popular appeal, however, in my view “I Have a Dream” was not King’s most potent and incisive speech. That distinction belongs, rather, to the speech he gave at the Riverside Church in New York on April 4, 1967, exactly a year before his assassination.

It was in the Riverside speech that he publicly announced his opposition to the U.S. war in Vietnam. For a long time, he had inwardly opposed the war but had never previously spoken against it in public. Now he felt his conscience demanded he speak out, and he thus titled the speech “A Time to Break Silence.”

King’s decision to declare his opposition to the war drew pointed criticism. Many of the American political leaders who supported him on civil rights turned against him; some even tried to smear him as a communist agent. But criticism also came from his fellow leaders in the civil rights struggle. They pleaded with him to reverse his decision, asking him not to risk jeopardizing their cause by stepping outside his proper domain. In their view, further progress in securing civil rights required that, with regard to the war, King continue to remain silent.

King, however, had a different view about his responsibilities. He saw his commitment to the cause of racial justice and his opposition to the war as integrally connected aspects of a single moral and spiritual demand, a demand that swelled up from the depths of his being as if by divine decree. In the speech he offers seven reasons for his decision to speak out against the war. Of these, the one he felt most pressing was his conviction that as a preacher and a man of God, he was obliged “to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation and for those it calls enemy” (p. 234).1 Whether it was Black Americans denied their civil and political rights or Vietnamese peasants decimated by U.S. bombing raids, it was the need to defend the full humanity of the victims that pricked King’s conscience and brought forth words of eloquence from his mouth and pen.

After explaining in detail his reasons for opposing the war, he next offers a sharp but salutary diagnosis of the underlying forces that drive American policy. This diagnosis takes us beyond politics into the spiritual domain, into “the soul of America,” which makes King’s critique even more cogent in relation to our own time. He decries the war, not only for the violence it inflicts on innocent lives, but because it is “a symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit.” He identifies this malady as a pernicious scheme of values that gives priority to “things” over people; specifically, a code of values that endorses the quest for wealth, profits, and property rights even when these pursuits lead to the oppression, death, and devastation of millions of our fellow human beings.

King locates, at the root of our cultural pathologies, “the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism.” The unity of these three evil forces figures prominently in King’s thought throughout his later years. He declares, in his Vietnam speech, that “this business of burning human beings with napalm … of sending men home from dark and bloody battlefields physically handicapped and psychologically deranged, cannot be reconciled with wisdom, justice, and love.” Then he delivers a stark warning: “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death” (p. 241) This message is especially crucial for us to heed today. Here in America we falter over a bill that would provide urgently needed programs of social assistance to poor and low-wage families, on the grounds that they are “too expensive”; yet we gladly heap close to $800 billion annually on our bloated military machine. Such a disparity is surely an offense to the moral consciousness and a betrayal of our constitutional obligation to provide for the common welfare.

In the final portion of his speech, King lifts his gaze from its focus on the immediate crisis of the Vietnam war and extends it to the broader dimensions of the human situation as he viewed it under the conditions of his own time; these conditions are still very much with us today. He speaks of how, all over the globe, people are turning against old systems of exploitation and oppression and are aspiring for new models of governance marked by justice and equality. He denounces the role of the Western nations, whose leading philosophers first envisaged the ideals of revolutionary justice, but which have now become the defenders of oppression, the foes of systemic transformation. He declares, with a provocative flourish, that “our only hope today lies in our ability to recapture the revolutionary spirit and go out into a sometimes hostile world declaring eternal hostility to poverty, racism, and militarism” (p. 242).

King goes on to sound the call for “a genuine revolution of values,” which entails that “our loyalties must become ecumenical [that is, universal] rather than sectional.” To preserve the best in our societies, he contends, “every nation must now develop an overriding loyalty to mankind [that is, humankind] as a whole.” And that means we must heed the call “for an all-embracing and unconditional love” for all people everywhere. King clarifies that what he means by the often-diluted word “love” is not “some sentimental and weak response,” but “that force which all the great religions have seen as the supreme unifying principle of life, the key that unlocks the door which leads to ultimate reality” (p. 242).

Despite the passage of 56 years since King delivered his speech at the Riverside Church, the message he conveys still rings true, indeed with astonishing prescience. Particularly astute was his insight into the deep, hidden, inextricable connections that unify the multiple crises we face in today’s world, even right here in our own country. King’s triple scourge of systemic racism, poverty, and militarism has to be extended to include ecological devastation (especially climate change), the drift toward authoritarian forms of government around the world (even here in the U.S.), and the rise of repressive, reactionary religious sects that encourage violence and seek domination through political alliances.

Even the supreme triumph of the civil rights era—the gain of voting rights by Black Americans—is now in grave danger. These gains were already weakened by the Supreme Court decision of 2013, which removed the need for “preclearance” of changes to voting rules in states with a history of racial discrimination. Over the past few months, the right to vote is being seriously eroded by new laws that permit voter suppression, election subversion, and partisan redistricting in ways that diminish the impact of voters from Black and other minority communities.

Another major Supreme Court decision, the Citizens United ruling of 2010, also delivered a blow to genuine democracy. The ruling lets corporations and wealthy individuals spend unlimited amounts of money on elections, thereby giving disproportionate weight to the interests of the ultra-wealthy over the concerns of ordinary citizens. The result has been to hand control over our political system to giant corporations and moneyed groups, with a corresponding reduction in the role the people have in determining who represents them and what kinds of programs are enacted. This has allowed vast disparities in wealth to grow still wider, such that here in the U.S. roughly 40 percent of the population is poor or low income, while just six men possess between them over $900 billion.

With the increasing rise of autocratic tendencies in American politics, the replacement of the rule of law by the rule of wealth, and the persistence of poverty and new manifestations of racism, our situation becomes increasingly dire, the future of American democracy ever more fragile. Since currents in American politics do not remain confined within our own borders, the impact of an autocratic takeover of the U.S. would inevitably spread across the globe, encouraging other aspiring autocrats to take control of their countries. Already strange partnerships are emerging among autocrats in distant lands.

All these worrisome developments call for a determined moral response, a response ultimately grounded in compassion and the affirmation of human solidarity. Delay is not an option. Here King’s words, toward the end of his Vietnam speech, become especially piquant: “We are now faced with the fact, my friends, that tomorrow is today. We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now. In this unfolding conundrum of life and history there is such a thing as being too late. Procrastination is still the thief of time” (p. 243).

The question we face here in the U.S.—as we flounder in our struggle against poverty, racism, devastating climate change, the erosion of voting rights, and the drift toward authoritarianism in politics and religion—is this: “Will we act in time, or will we look back, as King put it, ‘naked and dejected with a lost opportunity,’ forced to admit that we let the chance slip by and now it’s simply too late?”

1. All references are to the text of the speech in A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., edited by James M. Washington (HarperSanFrancisco, 1986).↩

Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi is the founder and chair of Buddhist Global Relief.